Why The Fed Won’t Cut Rates Any Time Soon

Summary & Key Takeaways:

While inflation is slowly heading lower, wage growth is cooling and the economy is slowing, we are far from levels that would support easy monetary policy.

In fact, based on the current inflation and employment data, monetary policy is right where it should be.

As it stands, there is little reason to expect rate cuts any time soon.

Higher for longer ladies and gentlemen.

The inflation fight is still not over

Inflation is heading in the right direction. But, from a monetary policy perspective, the fight isn’t over.

Few variables matter more to monetary policy than inflation, as we have learned in recent years, and although it is no longer the harbinger of pain it was last year, inflation remains stickier than many anticipated. Indeed, if we examine the various measures of inflation and their momentum through the lens of a three and six-month annualised growth rate basis compared to current year-over-year numbers, aside from Core PCE, the downside inflation momentum we have witnessed this year looks to be running out of steam.

What we can also discern from the above is much of the downside momentum we are seeing above is being driven primarily by Owners’ Equivalent Rent - the largest component of the CPI basket - in addition to the recent inflation volatility being spurred by the latest plunge in energy prices.

On the bright side, OER will continue to trend lower over the coming 18 months (detailed here), but the current rout in oil and gas prices is likely to only matter from a CPI perspective for the next month or two.

Given that wage growth remains a bit more stubborn than the Fed will like (more on this later), and my inflation leading indicator looks to be turning up, this suggests the downside force that is OER will be met by upside inflation pressures from the goods and services sectors.

Now, does this mean current inflationary pressures warrant additional rate hikes? No, I don’t think that’s the case either. If we compare the historical relationship between Core Inflation and the Federal Funds rate, with Core CPI tracking at 4% YoY a Federal Funds rate above 5% seems more than reasonable. If anything, relative to inflation, the path of monetary policy throughout the 2020s up until now has still yet to reach levels that historically would be considered tight.

Indeed, as we can see below, current inflation levels (Headline CPI and Core PCE) are more or less in-line with historical levels that have coincided with a peak in the Fed Funds rate. Importantly, just because we are at peak policy rates doesn’t mean they must come down anytime soon.

The jobs market is still tight

Similar to inflation, the labour market is slowly but surely cooling. However, it is difficult to argue it is anywhere near cool enough to warrant rate cuts.

On the positive side, job openings have rolled over dramatically from the highs in 2022 and are clearly trending in the right direction. However, not only are there still roughly ~1.3 jobs available for every unemployed person, but opening remains well above any pre-COVID levels while the number of unemployed persons has barely budged off cyclical lows. Such dynamics are typical of a tight jobs markets, and tight monetary policy is typical of a tight jobs market.

Of course, employment and inflation data are both backward looking. They are lagging economic indicators which show where the economy has come, not where it is headed. But, from a monetary policy perspective, it is the current status of the jobs market, inflation and economy as a whole that takes precedent.

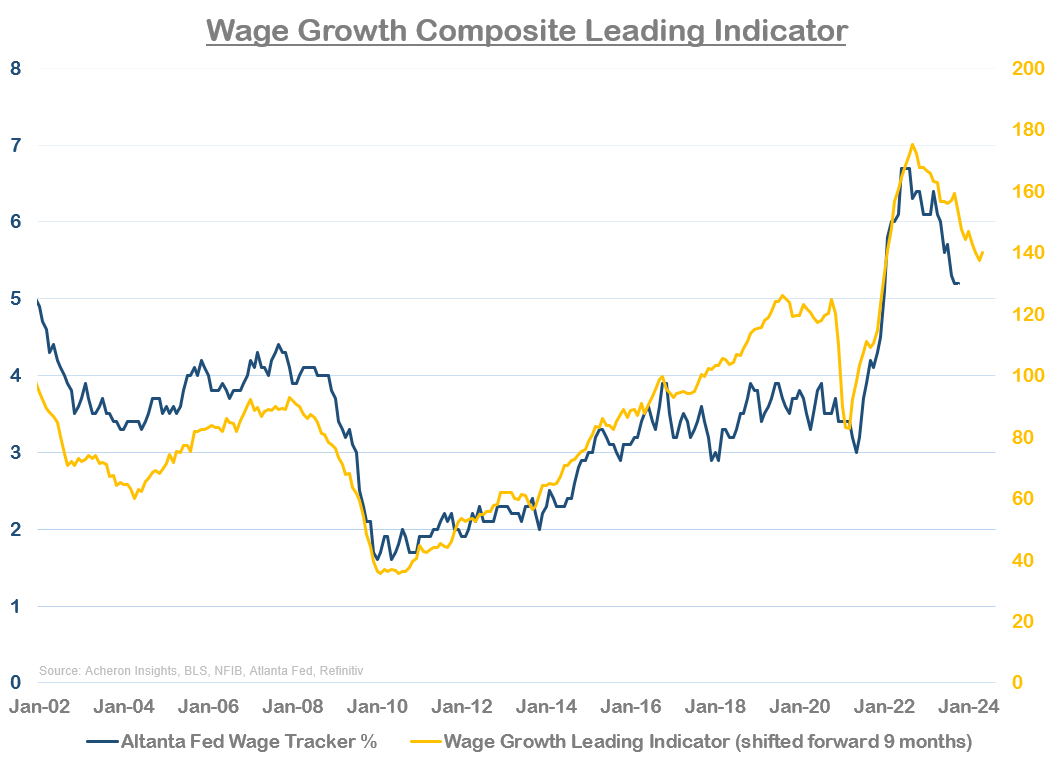

And while we are seeing downside momentum in many indicators of the jobs market, most notably job openings (as above), as we can see below, this isn’t universal. Wage growth momentum is clearly negative (with the Atlanta’s Fed’s wage growth tracker currently tracking at -2% on a three-month annualised basis), but it’s still growing at 5.2% on a year-over-year basis. Meanwhile, overall employment growth remains relative steady, while average hourly earnings (though showing slight downside momentum) is still growing at over 3% on all measures. This doesn’t look like a jobs market in need of rate cuts.

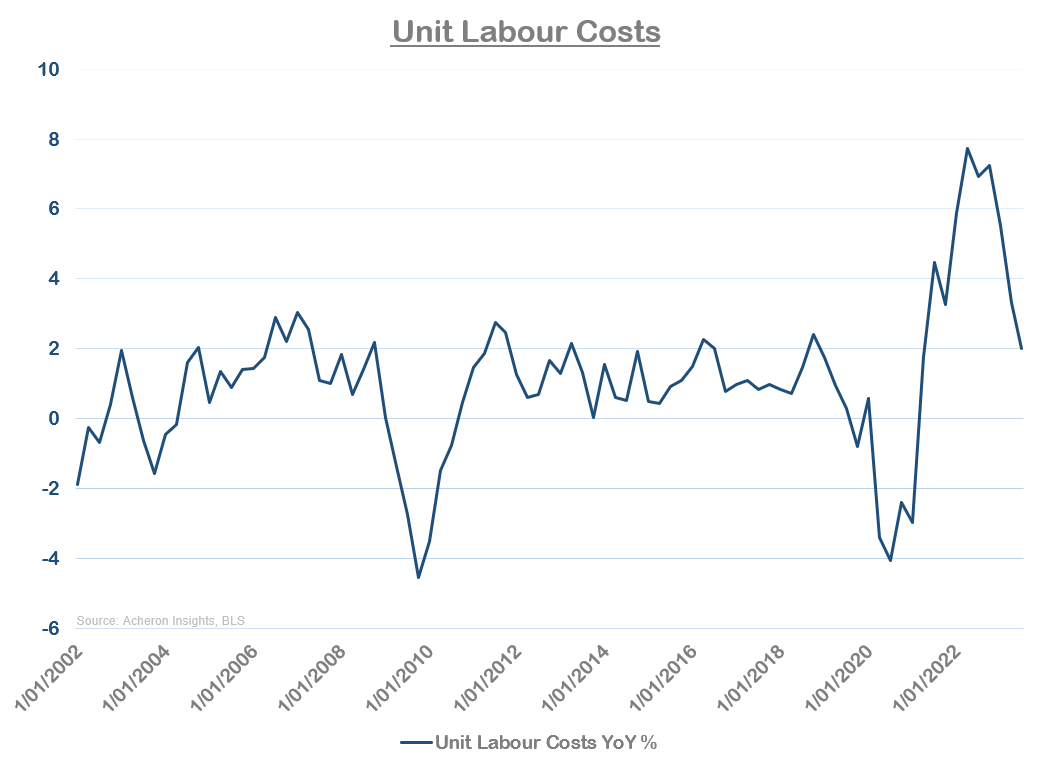

However, where the Fed will find some solace is in regards to Unit Labour Costs, which are a measure of wage growth in excess of labour productivity. By netting out the effects of productivity growth, this measure captures the actual cost a business pays its workers per unit of output, and is a variable in which central bankers put a great deal of emphasis in their forecasts and decision making. For the Fed, this is what a soft landing looks like, low unemployment coupled with wage growth returning to normal levels. We still have a way to go however on this regard.

But, when I look at the leading indicators of wage growth via my composite leading indicator below, the swift decline in wages we have seen thus far looks to have gotten a little ahead of itself for now.

And while this downtrend in wage growth and unit labour costs is clearly enough to avoid additional rate hikes, the jobs market overall is still a way off allowing for any outright cuts. November’s jobs numbers from the BLS very much attest to this. The unemployment rate moved back down 20 bps to 3.7%, a number still roughly 1.5% below levels that coincide with historical rate cuts.

The jobs market will continue to weaken, but given where the rate of employment growth is at present, it is far from suggesting any kind of rate cuts are needed any time soon.

The economy is still holding up

Just like the jobs market and current inflation trends are suggesting, the economy overall does not appear to be one crying out for easier monetary policy. In fact, as I have detailed much this year, the economy is still humming along nicely.

Are we seeing signs of weakness beginning to show up in hard economic data? Absolutely. Particularly in the cyclical areas such as manufacturing and retail sales. And although I hold the view we could see a fairly swift downturn in economic growth as we enter 2024 (detailed here), I’m hesitant to say with any certainty it will akin to a recession or simply an economic slowdown, nor is such a downturn yet to show up broadly within any hard economic data.

Outside of industrial production whose deterioration is reflective of the struggling manufacturing sector, momentum in the major areas of the economy in the form of consumption and incomes (in addition the employment) can attest to the economic resilience we have seen and continue to see.

No time to cut

As we have seen, assessing the outlook of the economy through the lens of the Fed’s two mandates - inflation and employment - as well as the current state of the business cycle suggests the Fed will find it very difficult to justify anything other than higher for longer policy rates for the foreseeable futures.

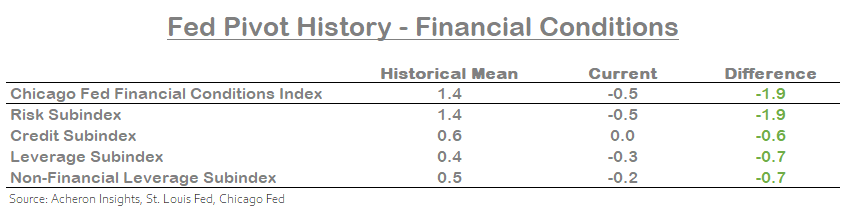

If we extend this analysis a little further to look at other factors that have influenced monetary policy in the past, such as asset prices and credit conditions, regardless of the cyclical outlook for either, the recent move higher in stocks and move lower in credit spreads are again providing the Fed little scope for any dovishness.

In fact, what we have seen throughout November is a significant easing in financial conditions. Given where inflation and employment are both current residing, financial conditions would need to get much worse from here for the Fed to even entertain easier monetary policy.

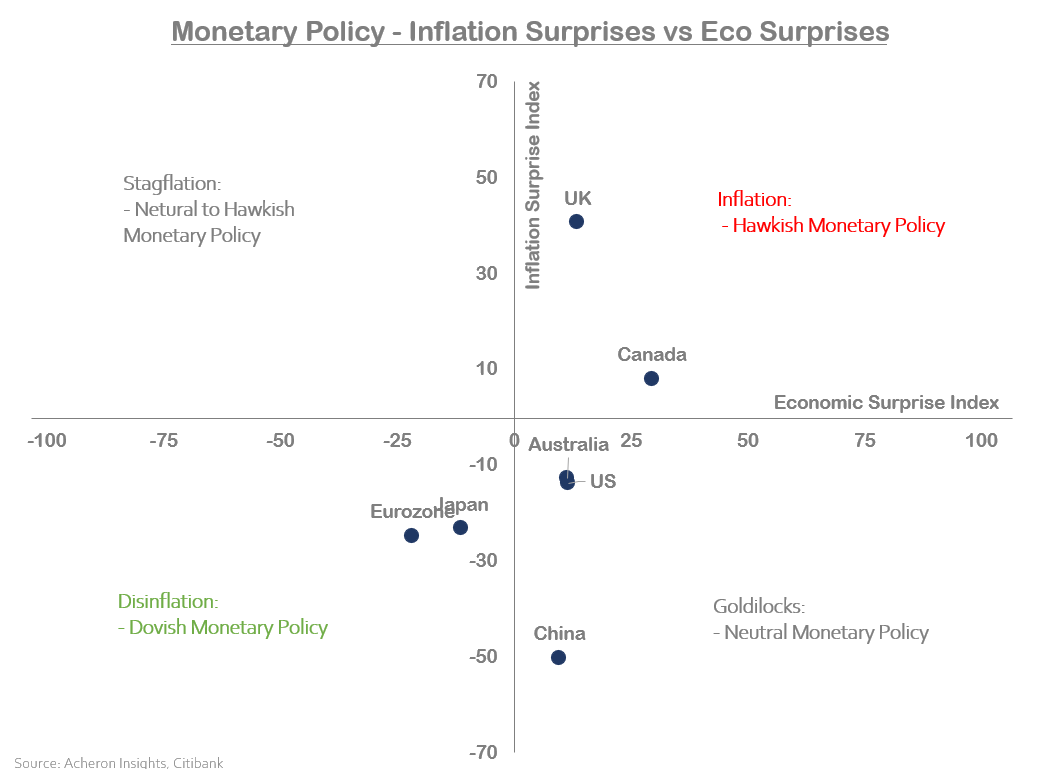

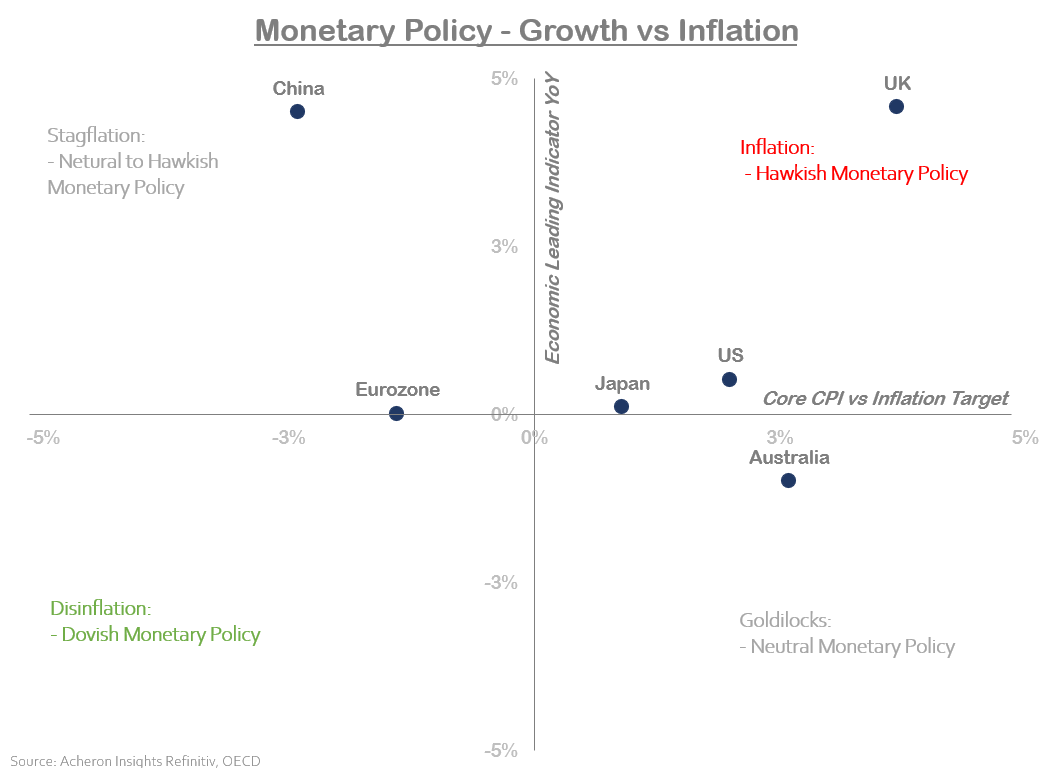

A similar message can be gleaned by assessing inflation and economic surprises for the US. As we can see below, although upside inflation surprises no longer look to be an issue for the US economy, we still need to see economic surprises move meaningfully lower before both suggest dovish monetary policy is on the cards.

The same can be said when comparing economic growth and Core CPI relative to its target.

Furthermore, comparing the trend in unemployment versus the trend in inflation yields a similar message.

A stable financial system

Another key ingredient dictating monetary policy intervention in markets is financial stability, or rather, instability. We saw the classic Fed reaction function during the regional banking crisis earlier this year when they were forced to backstop the deposit base. Aside from this hiccup, things in the world of financial stability and contagion are seemingly on solid footing, despite continued rate hikes and QT in the months since, at least for now.

One important key in assessing the stability of the financial system is looking at the level of commercial bank reserves in the system. In isolation, QT should suck reserves off bank balance sheets, but, given the huge piles of cash that remain in the Fed’s reverse repo (RRP) facility, the QT and Treasury issuance that would normally be funded via commercial bank reserves is instead largely being offset by a reduction in the RRP (as money market funds move out of RRP and into freshly minted Treasury bills). As such, commercial bank reserves have actually increased over the past six months.

I’ve heard many people much smarter than I opine that reserves of about $2.5 trillion should be sufficient to ensure the financial system runs smoothly. Given reserves currently reside well above this level (to the tune of around $1 trillion), in addition to the still significant reverse repo balance, the Fed likely has plenty of scope to continue QT before things start to break.

In terms of commercial bank deposits, the story here is a little different. As we saw in the run-up to the regional banking crisis earlier this year, depositors at commercial banks continue to move monies to higher yielding alternatives elsewhere.

Which makes it unsurprisingly the Fed’s Bank Term Funding Program which was introduced to fill the void of fleeing deposits continues to be heavily relied upon by commercial banks. But, so long as this is the case, any hole this previously made in the financial system has likely been plugged for now.

And finally, the final area of market stability I like to keep an eye on is the demand and supply imbalance in the Treasury market. I detailed in depth here my analysis on the outlook for US yields, and as a result of the Fed undertaking QT, a strong dollar disincentivising foreign central banks to purchase US debt, a Japanese central bank taking steps that is slowly incentivising capital to move back to Japan from the US, in addition to the outlook for the US deficit, so long as the Fed is no longer a buyer of Treasuries it is likely there will be an oversupply of government debt relative to demand. To fill this gap, the onus has fallen on the US private sector, with hedge funds being a particularly large buyer of Treasuries as they deploy the classic basis trade.

In all, should yields spike meaningfully as a result of these dynamics (which could be exacerbated by hedge funds then selling bonds as they are forced to unwind the basis trade - selling Treasury futures and buying underlying Treasuries), this seems the most likely event to which the market will bring the Fed to its knees.

How high must yields go to cause such an intervention? I’d say a fair bit higher from here. Given the level of cash remaining on commercial bank balance sheets and the Treasury’s willingness to reduce the duration of its issuance to incentivise drawing down the RRP to soak up the issuance, and given the fact that an economy with nominal GDP of over 6% should easily be able to hand yields of over 4%, I’d say this isn’t a meaningful threat to the financial system for now.

Unsurprisingly, the market is pricing in rate cuts…

Similar to the equity markets, short-term rate markets are looking increasingly priced to perfection. Markets are pricing in a ~44% chance of rate cuts as early as March, and a ~77% chance of a rate cut by May.

Looking further out, current SOFR futures are pricing in a Fed Funds rate of nearly 100 bps lower come the end of 2024.

While I agree it is probably unlikely we will see additional rate hikes anytime soon, to me, this outcome is a little too ambitious. The market is notoriously wrong in their predictions for the path of future monetary policy, and for the reasons detailed herein, I expect this time to be no different.

. . .

Thanks for reading!

If you would like to support my work and continue to allow me to do what I love, feel free to buy me a coffee, which you can do here. It would be truly appreciated.

Regardless, feel free to share this with friends and around your network. Any and all exposure goes a long way and is very much appreciated. Thanks again.