Evaluating The State Of The US Economy

Summary & Key Takeaways

Over the past couple of months, we have seen a clear downtrend emerge in the coincident measure of economic growth, suggesting we are on the path to recession. Inflation is also clearly rolling over.

However, this is not the case within the labour market nor the services sector, both of which remain robust.

Likewise, household balance sheets remain strong, meaning their ability to withstand higher borrowing costs is likely to result in this cycle playing out slower than expected.

We are on the path to recession

The purpose monitoring coincident economic data and market developments is it allows us to best determine the trend of the business cycle and assess which parts of the economy we are seeing strength or weakness. To do this, we need to monitor various hard data points from all corners of the economic landscape. These include consumption trends, industrial production and manufacturing, real income growth and employment. Despite nearly all of these data points being coincident and lagging in nature - which means they bear little for the future trend of the business cycle - they are important to understand and monitor nonetheless, particularly as it portends to monetary policy decision making.

An excellent way to quickly gauge the trends of these coincident data points is by looking at the momentum of their respective growth rates. As we can see below, what has become most notable of late is the recent downward trajectory of industrial production, real personal consumption, real manufacturing and trade sales, as well as retail sales. Regarding consumption and industrial production in particular, up until only a couple of months ago these areas of the economy were holding up quite well. Clearly, this is no longer the case. Outside of employment (which we will discuss in greater detail below), the coincident data is beginning to reflect what the leading indicators of the business cycle have been signaling for some time; we are on the path to recession.

We can analyse these trends in greater detail as follows by charting the six-month annualised growth rate of the respective coincident data points. As we can see, the business cycle peaked at an extraordinarily high level back in early 2021 before effectively trending sideways for much of 2021 and 2022. Most notably, industrial production has rolled over significantly in the past month or two and now finds itself below its three-year trend, while the same can largely be said of real personal consumption growth.

The collapse in consumption even more pronounced when assessing retail sales, which has now inflected negatively on a six-month annualised growth rate basis to its lowest level since 2015 (COVID lockdowns aside).

Alas, it is not all doom and gloom. Considering we have recently seen the largest rise in tightening of financial conditions in over four decades, there remains a remarkable level of robustness within the US economy. One of the main drivers of the growth slowdown thus far has been the negative trend in real income growth as wages have struggled to keep up with inflation. Fortunately, with inflation now decelerating at a faster pace than wages, real incomes are beginning to inflect positively. This is good news for the consumer, and is one of the reasons why we have seen real manufacturing and trade sales too inflect positively.

Taking a step back, if we were to compare the current growth in these various data points versus their historical averages at the commencement of all recessions post-WWII, the findings here are very informative. As we can see below, outside of employment, the coincident measures of economic growth are already at or near levels that coincided with past recessions. Given the NBER uses many of these data points as inputs to their recessionary determination (though they do so with a modicum of subjectivity), one could easily infer we are currently in recession. Of course, we won’t know for some months still given how recession dates are determined after the fact, this is nonetheless an interesting observation and help provide important historical context as to where we currently reside within the business cycle.

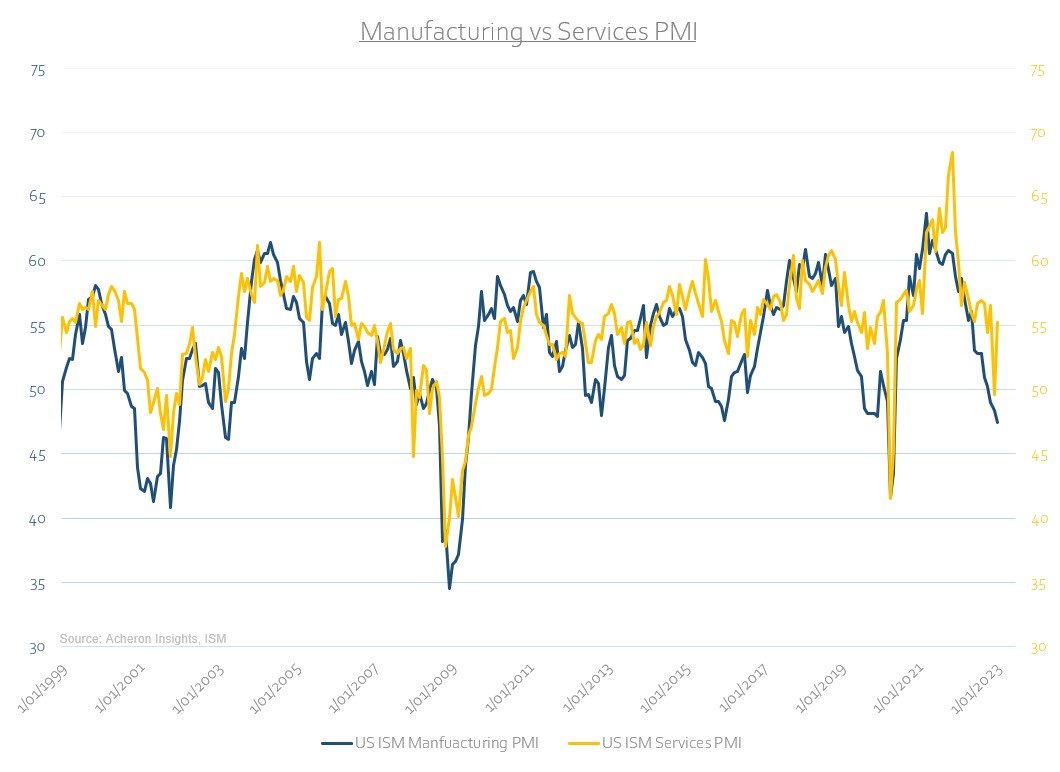

Another metric commonly used as a proxy from the business cycle is the Institute of Supply Management’s manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index (PMI), which is a survey taken by a large number of manufacturing firms throughout the US and provides an excellent indicator of the trends therein. Every time the manufacturing PMI has reached a sub-45 level, we have entered recession. With the latest reading coming in at 47.4, we are getting mighty close. Clearly, the manufacturing sector has taken the brunt of this cyclical slowdown thus far.

A similar trend can be observed using the Economic Cycle Research Institute’s (ECRI) Coincident Economic Index, which provides a broad-based measure of coincident growth. Every negative year-over-year growth reading in ECRI’s coincident index has coincided with recession. As of this writing we remain in positive territory, suggesting much of the slowdown may still be ahead of us.

Strength in the services economy continues

While we are beginning to see a fairly broad-based decline in economic growth, this has predominately been driven by a slowdown in the manufacturing sector as opposed to the services sector. It is very important to distinguish between the two as the services sector is responsible for roughly 80% of all job creation and over 60% of GDP, compared to around 10-20% from the manufacturing sector. While the manufacturing sector is a large driver of the cyclicality of the business cycle, the dynamics within the services sector are what define the overall trend in economic activity.

Clearly, as we can see below, the services sector remains strong and robust. Services consumption is still growth 8% pa - a level well above any reached post-GFC - while goods consumption growth has fallen to the low single digits. Likewise, if we compare the ISM manufacturing PMI to the services PMI, the latest reading in the latter was over 55 (expansionary territory), while the manufacturing PMI came in below 48 (contractionary territory).

The Labour market is still historically tight

Where the economy also continues to surprise to the upside is within the labour market. Though it is prone to heavy revisions after the fact, both employment and wage growth remain stubbornly high. Employment growth in particular continues to prove robust, with the six-month annualised growth rate still above any level seen from the post-GFC period up until the COVID-19 pandemic.

The reason of course is the historic tightness we are seeing, as job openings remain materially above unemployed persons. Neither are yet to show any clear sign of normalising.

Most recently, January’s employment data proved particularly strong, and as a result, momentum within a number of data points that capture the labour market dynamics continue to inflect positively. Outside of private payrolls, the three-month annualised growth in non-farm employment, average weekly hours and average hourly earnings are well above their respective five-year averages and six-month annualised growth rates. The labour market is the domino that has yet to fall, and ultimately, how long it holds up will play a large part in whether we do eventually enter a recession.

Inflation is rolling over

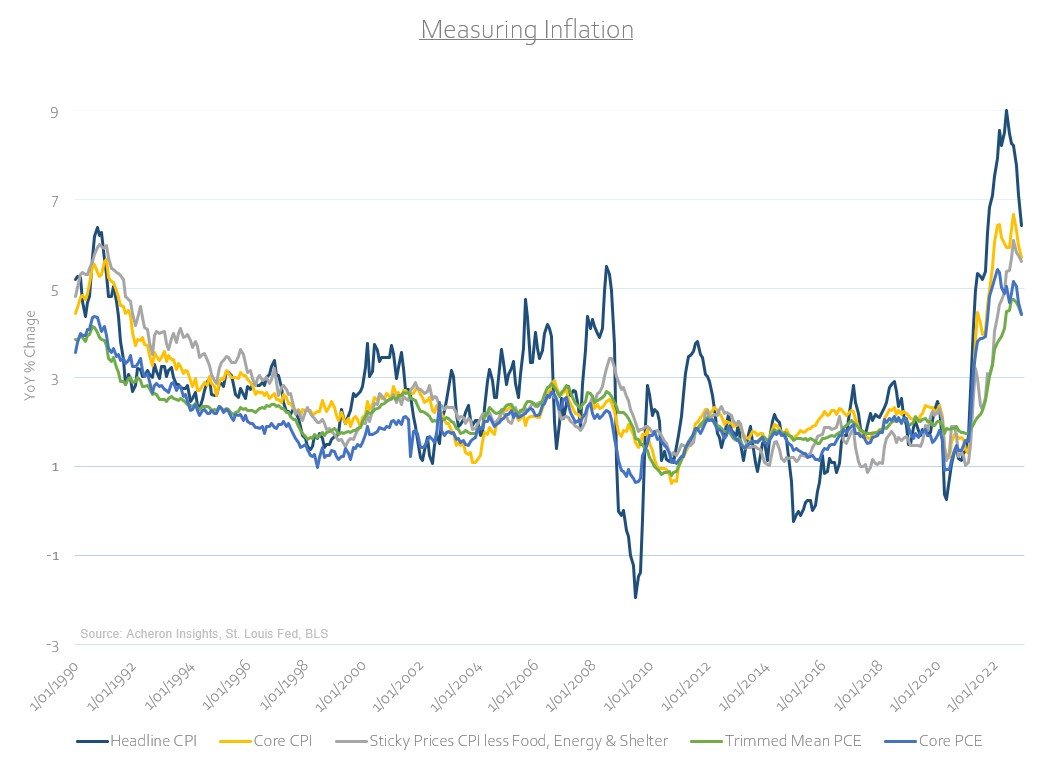

As I detailed in depth recently, we are now seeing clear signs of a broad-based deceleration in inflation. As a result of outright deflation in many measures of goods CPI, along with falling energy inflation and soon-to-be falling food inflation, headline CPI in particular is slowing at as fast a pace as it accelerated throughout 2021 and is likely to continue to do so for at least the next few quarters.

Inflation momentum is now strongly pointed downward. Headline CPI is growing at a sub-2% three-month and six-month annualised rate, while core CPI and core PCE are hovering around the 3% level. What’s more, services CPI ex-shelter has decelerated markedly to a 0.9% three-month annualised rate of growth, with this measure being one Powell has highlighted recently as being front and square on the Fed’s radar.

Whether we see CPI below 2% at some point this year remains to be seen. Ultimately, this will be determined by wage growth, with services inflation and rent inflation in particular being primarily a function of wage growth. As we have seen, the labour market continues to surprise to the upside, and although the leading indicators of wages suggest they should roll over at some point this year, we are yet to see this show up in the coincident data.

Households balance sheets remain strong, but cracks are forming under the surface

What has surprised many during this cycle has been the ability of households and corporations to withstand the rapid rise in interest rates that were seen as to be materially harmful. While this may indeed prove true, for the most part the economy has held up surprisingly well considering the rapid rise in borrowing costs we have seen. The primary reason for this robustness has been the incredible strength within the household sector. Not only did household net worth as a percentage of GDP peak at levels well above its recent trend, but households are still flush with cash and the overall size of ither balance sheets remain materially higher than at any point pre-COVID.

When you have strong cash balances you are able to better withstand the impacts of higher borrowing costs. This is particularly the case within the housing market, as the rise in mortgage rates has been more impactful to prospective buyers than it has to existing home owners, while the fact that the majority of US mortgage loans are fixed has also helped. As it stands, debt service payments relating to mortgage debt and overall household debt remain near multi-decade lows. This is one major reason why this cycle is playing out slower than expected.

However, we are beginning to see signs of stress emerge. The negative effects associated with higher rates can only be held off for so long. Not only has the fall in asset prices begun to impact consumption, but the recent surge consumer credit is worrisome.

Households have increased their reliance on credit cards and the like to support their cost of living as a result of inflation growing in excess of wages. As a result, consumer credit growth has soared to two-decade highs and showing no signs of slowing, while the ability of households to service consumer debt is also nearing record highs.

As the reliance on credit increases, banks generally become less willing to be providers of said credit. This is why we are seeing banks tighten lending standards for both credit card loans and consumer loans as a whole.

And as such, interest rates on credit cards have quickly spiked to their highest level in over three decades.

Which unsurprisingly has resulted in the largest year-over-year spike in delinquency rates on credit card debt and consumer debt since the GFC.

As credit conditions deteriorate and access to credit is made more difficult for the masses, these tighter credit conditions will drive spending lower, thus accentuating the slowdown in growth. Unfortunately, as the credit cycle plays out, volatility is likely to follow suit.

While consumers remain on solid footing overall and have largely been shielded from the rise in mortgage rates thus far, the stress in the consumer credit sector are worrying. Should they continue, this will undoubtably lead us down the path to recession.

Putting it all together

To recap, outside of employment and the services sector, economic data is beginning to roll over and approach recessionary levels. Reliance on consumer credit is soaring and as a result, consumption, manufacturing and industrial production are taking a significant hit. Because this cycle may play out slower than expected given the persistent strength in the labour market, falling inflation and fairly robust household balance sheets overall may result in the Fed remaining tighter for longer. Hiking into a slowdown is not the path to a soft landing. In order to allow the Fed to pivot dovishly, we need to see labour market weakness. Unfortunately, this still may not be a story for the second half of 2023.

. . .

Thanks for reading!

If you would like to support my work and continue to allow me to do what I love, feel free to buy me a coffee, which you can do here. It would be truly appreciated. .

Regardless, feel free to share this with friends and around your network. Any and all exposure goes a long way and is very much appreciated. Thanks again.